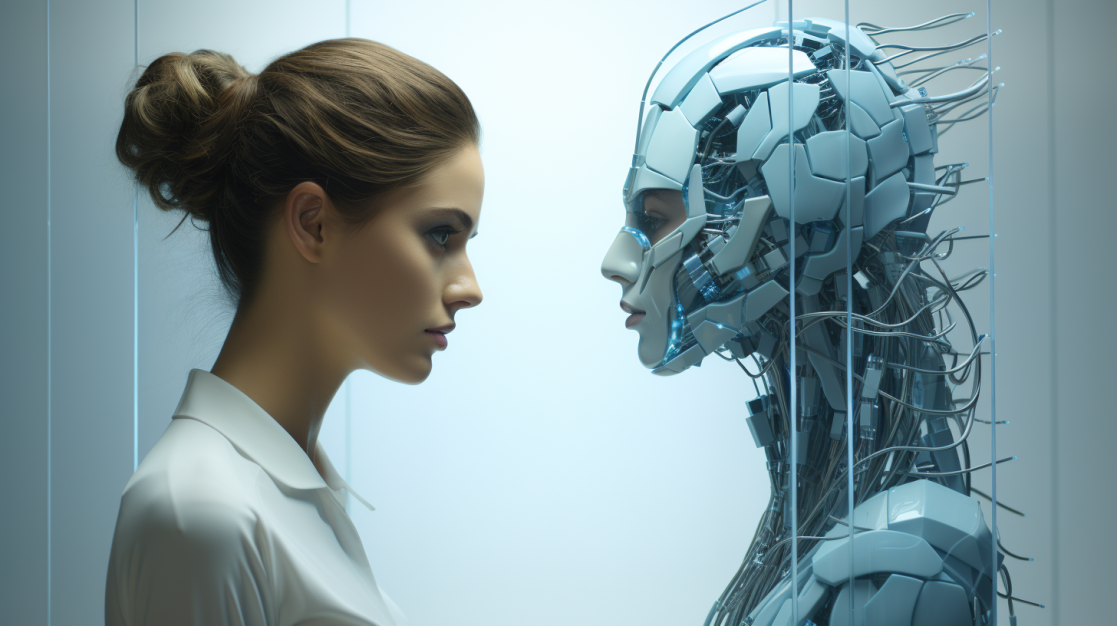

Healthcare professionals often serve as gatekeepers, controlling access to medical care, procedures, and information. This gatekeeper role is essential for coordinating care, managing costs, and protecting patients. However, some healthcare providers take gatekeeping too far, limiting access beyond what is appropriate. This overzealous gatekeeping manifests in two primary ways: restrictive policies in professional medical settings and paternalistic policing of health information on social media. While gatekeeping is necessary, an overly rigid approach can negatively impact patient care and satisfaction. Healthcare professionals must thoughtfully balance access and regulation to serve patients’ best interests.

The Gatekeeper Role in Professional Medical Settings

In clinics, hospitals, and health systems, healthcare providers act as gatekeepers by determining who can access specialty care, diagnostic tests, and treatments. They decide if a referral to a specialist is warranted or if an expensive diagnostic test is essential. This gatekeeping allows healthcare professionals to coordinate care, promote cost-effective practices, and protect patients from unnecessary procedures.

However, some providers interpret this role too strictly, refusing referrals or tests when patients legitimately need them. For example, a primary care physician may deny a referral to a rheumatologist for a patient with potential lupus, insisting the symptoms are not definitive enough. Alternatively, an emergency room doctor may refuse to order a CT scan for a patient with mild traumatic brain injury symptoms, stating it is not protocol. This overly restrictive gatekeeping can stem from outdated paternalistic attitudes, financial incentives, or simple inertia.

Rigid gatekeeping policies can delay diagnosis and treatment, allow diseases to progress, and lead to poorer health outcomes. For instance, a study found that primary care physician gatekeeping was associated with increased mortality and complications for patients with cancer compared to direct access to oncologists[1],[2]. Another analysis found that overly restrictive referral policies for bariatric surgery may lead to significantly increased mortality[3],[4]. Gatekeeping, when taken too far, at best, delays access to essential care and, at worst, costs lives.

Beyond serious diseases, excessive gatekeeping also impacts the quality of life for patients with chronic conditions. A survey of clinicians in Canada showed that 83% of them found it difficult to refer to pain clinics, with one of the significant barriers being the difficulty locating and administration associated with getting referrals to pain specialists[5],[6]. Many patients describe the referral process as a “constant battle” leading to uncontrolled pain and frustration. Gatekeeping in this context does little to improve care coordination and worsens patients’ daily well-being.

Gatekeeping policies also disproportionately affect marginalized populations[7]. A study on youth access to mental healthcare found that racial and ethnic minority youth were less likely to obtain needed services than white youth, partially due to gatekeeping barriers[8]. Other research shows that lower-income patients face more hurdles getting specialist referrals than affluent patients[9]. Excessive gatekeeping exacerbates health disparities.

In these examples, healthcare providers wrongly assume the gatekeeper role gives them unilateral power over healthcare decisions. However, patients have essential rights, including access to care, make informed choices, and consent. Reading the evidence in the open literature leads one to argue that overly restrictive gatekeeping violates fundamental patient rights and shared decision-making principles[10],[11]. Healthcare providers have a duty to inform and empower patients, not act as authoritarian gatekeepers against their wishes[12].

A distinct form of problematic gatekeeping occurs when healthcare professionals police the health information that patients receive on social media. As patients increasingly use social media for health education and advice, some healthcare providers try to control this information tightly, chastising or shaming patients for accessing non-approved resources. However, this overly paternalistic gatekeeping can backfire, undermining patient trust.

For example, a healthcare provider may reprimand a patient for joining an online support group for their chronic condition, stating they should not trust unverified advice from strangers online. Nevertheless, these online communities provide valuable peer support and experiential knowledge beyond what any individual provider can offer. Dismissing them removes a vital coping resource.

Similarly, a doctor may criticize a patient for using mobile health apps or patient-driven data tracking. For instance, they may claim continuous glucose monitoring devices are “only for diabetics” when impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) patients use them for other purposes like diet management [13]. This gatekeeping ignores the potential benefits of patient-driven tracking, including improved self-efficacy, motivation, and insights.

Healthcare providers may also chastise patients for accessing direct-to-consumer testing options like at-home genetic testing or lab tests without a doctor’s order. They caution that these tests are inaccurate or unnecessary, urging patients to access testing only through provider-approved channels. However, this paternalistic stance must grasp the empowering potential of appropriately sourced direct access testing.

These examples of social media gatekeeping stem from a fear of losing professional authority. In reality, healthcare expertise is not a zero-sum game. Patients accessing social media health resources does not diminish the provider’s knowledge; rather, it represents patients taking the initiative for their health. Dismissing this engagement damages productive patient-provider partnerships.

Striking a Balance: Solutions for Nuanced Gatekeeping

These two faces of problematic gatekeeping place healthcare professionals in a difficult position. They must judiciously manage healthcare resources and information without overextending their gatekeeper role. Navigating this balance requires shifting attitudes and practices.

First, providers must view patients as partners, not passive care recipients and accept patients’ right to access information, ask questions, and make choices. Gatekeeping should empower, not restrict, patients.

Next, providers must adopt a patient-centered approach focused on open communication and shared decision-making. Care providers should involve the patient in discussing risks, benefits, and alternatives before making mutual decisions. Patients may have valid reasons for seeking specialty care, additional testing, or online health resources. Exploring these motivations and priorities together is better than unilateral gatekeeping.

Additionally, primary care providers and specialists should collaborate to establish reasonable referral protocols that do not delay necessary care. Referral criteria should undergo regular revaluation to ensure appropriateness. Providers must also consciously recognize how biases or financial incentives may influence their gatekeeping and referrals.

For social media gatekeeping, providers need better education on the value of online patient communities, self-tracking, and direct access testing. While risks exist, the potential benefits warrant a nuanced discussion, not blanket dismissal. Providers should guide patients in evaluating online resources rather than prohibiting them.

[1] Vedsted, P., & Olesen, F. (2011). Are the serious problems in cancer survival partly rooted in gatekeeper principles? An ecologic study. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 61(589), e508–e512. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X588484

[2] Sripa, P., Hayhoe, B., Garg, P., Majeed, A., & Greenfield, G. (2019). Impact of GP gatekeeping on quality of care, and health outcomes, use, and expenditure: a systematic review. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 69(682), e294–e303. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X702209

[3] Imbus, J. R., Voils, C. I., & Funk, L. M. (2018). Bariatric surgery barriers: a review using Andersen’s Model of Health Services Use. Surgery for obesity and related diseases: Official Journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery, 14(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2017.11.012

[4] Zevin, B., Sivapalan, N., Chan, L., Cofie, N., Dalgarno, N., & Barber, D. (2022). Factors influencing primary care provider referral for bariatric surgery: Systematic review. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 68(3), e107–e117. https://doi.org/10.46747/cfp.6803e107

[5] Lakha, S. F., Yegneswaran, B., Furlan, J. C., Legnini, V., Nicholson, K., & Mailis-Gagnon, A. (2011). Referring patients with chronic noncancer pain to pain clinics: survey of Ontario family physicians. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 57(3), e106–e112.

[6] Reinking, J. C., MD. (2011, December 28). The ABC’s of Pain Clinic Referrals. https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com. https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/resources/practice-management/abcs-pain-clinic-referrals

[7] Dahlhamer, J. M., Lucas, J. W., Zelaya, C., Nahin, R. L., Mackey, S., DeBar, L., Kerns, R. D., Von Korff, M., Porter, L., & Helmick, C. G. (2018). Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Adults — United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(36), 1001–1006. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2

[8] Lu, W., Todhunter-Reid, A., Mitsdarffer, M. L., Muñoz-Laboy, M., Yoon, A. S., & Xu, L. (2021). Barriers and Facilitators for Mental Health Service Use Among Racial/Ethnic Minority Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Literature. Frontiers in public health, 9, 641605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641605

[9] Arpey, N. C., Gaglioti, A. H., & Rosenbaum, M. E. (2017). How Socioeconomic Status Affects Patient Perceptions of Health Care: A Qualitative Study. Journal of primary care & community health, 8(3), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131917697439

[10] Forrest C. B. (2003). Primary care in the United States: Primary care gatekeeping and referrals: effective filter or failed experiment?. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 326(7391), 692–695. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7391.692

[11] Willems, D. L. (2001). Balancing rationalities: gatekeeping in health care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 27(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.27.1.25

[12] Rotar, A. M., Van Den Berg, M. J., Schäfer, W., Kringos, D. S., & Klazinga, N. S. (2018). Shared decision-making between patient and GP about referrals from primary care: Does gatekeeping make a difference? PloS one, 13(6), e0198729. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198729

[13] Personal experience of communication between Patient and NHS HCP on Facebook Forum.